Once, I stayed the night in the most haunted room of the Virginian Hotel in Medicine Bow, Wyoming. The hotel is an oddity, an elaborate Edwardian style hotel from 1911; stone masonry and luxury built into the whole building gives off an air of the old, wilder, west.

Medicine Bow is on a stretch of highway that used to be the only road through the area. Since I-80 was built, this highway is more of a back-road. Most people in this region pass right by Medicine Bow on their way to Casper or the nearby recreation reservoir in Alcova.

It sits just a few miles from the famous Independence Rock from Oregon Trail’s days, Medicine Bow thrived in the days when the railroad brought people and goods from all over the country. Nowadays, the town is a lot smaller and a lot sleepier. Many buildings stand proudly in the community with well-cared-for plots of land and art installations made of metal and time.

My experience in the Virginian was one I’ll never forget. I was told by locals that it was built in haste as a sort of tourism draw for the bustling city– before the interstate would be routed away from it- after the Virginian, the book, was a huge success.

Back then, I thought I’d make that into a podcast– visiting Wild West hotels with ghosts and learning their stories– So I knew there was more than one spirit to encounter at the old hotel.

My room was on the third floor, the “most haunted room” which many hotel workers assured me was one they preferred not to be in alone. The old legends say that room and the one across the hall were hotbeds of activity and that the male spirit there was more of a prankster than an outright ghoul.

His most favorite thing to do, after all, was to open doors for any ladies staying in the hotel. Chivalry might be dead, but at least it’s still practiced by the dead.

Another specter was that of a young woman who reportedly jumped from her demise from the second floor window right outside in the hallway on the third floor. Legend says she was distraught because her fiance didn’t arrive on the train when he said he would. The legend also says that the fiance arrived only two days after, having been stuck at another rail station for longer than he’d anticipated.

The only ghosts I saw at the Virginian, unfortunately, were the ghosts of a little childhood fun– When I went up to my room from the saloon, having been talking about ghosts the whole time, I found things awry and amiss on the third floor. The room across from mine had all of the sheets strewn across the hotel. A potted plant was leaning up against my door. A barstool was put in my way to my room, and so was an open book.

For those wondering, the book was a generic romance novel, nothing special, but it all scared the daylights out of me when I went up, alone, to sleep on the third floor. Did I mention I was the only one staying in the historic hotel that night? The only others were in a detached motel building, and I was alone with the ghosts of the Virginian.

I didn’t sleep much, but that might have been more because it was November and the heat didn’t reach all the way to the third floor than any spirits– either from the saloon downstairs or elsewhere.

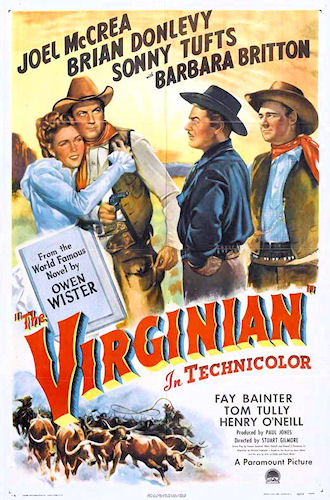

You might have heard the name “The Virginian,” before. Maybe you’ve seen other hotels or locations named after the same story— or maybe you watched TV in the 1970s when the famous Virginian TV show was live. Maybe you’ve heard of Owen Wister, but you’re unsure what his impact was on Wyoming.

The Virginian is a name that means a lot to Wyomingites. If you’re not familiar with Owen Wister’s work or the multitude of Westerns or TV shows about the anonymous man from Virginia— The book was written in 1902 and was written in and about the Cowboy State.

See, the first chapter of the Virginian shows our narrator being picked up from the Medicine Bow, Wyoming Train station depot– which today stands as the Medicine Bow Museum and has a full wing dedicated to the popular TV show from the 1970s.

There’s so much more to the Virginian, the book. Some say it’s the very first Western Novel ever published. It’s credited with creating the archetypal Cowboy figure in future media.

Half the fun comes from the fact that the book was the product of months and months of travel and study in the Wilds of Wyoming – only barely made a state a few years prior. Some of the usual suspects made appearances in the Cowboy state at that time as well., a president who liked fishing, an outlaw who befriended an author, the very notion of a Cowboy Poet and the way Wister expressed those qualities. The Virginian was nameless, but his creator’s name would be remembered for centuries.

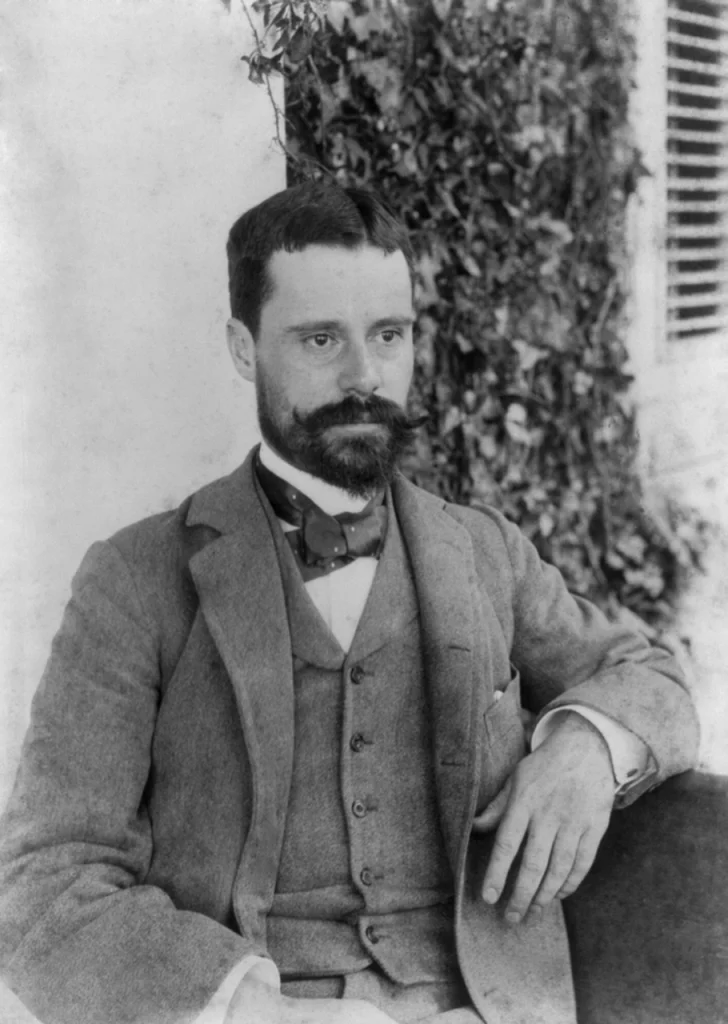

Owen Wister’s life was as wild as his stories would imply. Born in the 1860s in Pennsylvania. He attended conservatories overseas and Harvard University before his writing career took off with a parody he wrote about the Swiss Family Robinson— So well received, in fact, that Mark Twain himself would write to Wister to congratulate him on his writing.

Wister made his first trip to the Cowboy State before it was even considered a state. The Wyoming territory called to wister in 1885 and he would spend many summers in the wilds of the territory, making friends with ranchhands, business proprietors and politicians alike.

Like many men on the frontier in the 1910s, he formed a close friendship with Theodore Roosevelt in his travels. The two friends shared a love for the untamed wilderness and rough-and-tumble personalities of those who chose to live and work there.

Wister passed in 1938 after a life well lived and a legacy secured with an autobiography of President Ulysses S. Grant and his most famous work- The Virginian.

The Virginian is about a man from the South working as a ranch hand on a fictional cattle ranch near Medicine Bow. He is the first of many you may have seen that carried the archetype of the silent, longer, lawful cowboy. Parts of the novel were based on the real-life Johnson County Cattle War, when local ranchers defended their land from encroaching big ranch companies.

Wister tells the story in his foreward of the cowboy he knew and based the story of The Virginian on. He said:

“Sometimes readers inquire, Did I know the Virginian? As well, I hope, as a father should know his son. And sometimes it is asked, Was such and such a thing true? Now to this I have the best answer in the world.

Once a cow-puncher listened patiently while I read him a manuscript. It concerned an event upon an Indian reservation. “Was that the Crow reservation?” he inquired at the finish.

I told him that it was no real reservation and no real event; and his face expressed displeasure. “Why,” he demanded, “do you waste your time writing what never happened, when you know so many things that did happen?” “

So the Virginian may have been a real cowhand during Wister’s search through the Wild West for his story, but the stories he told were pulled from hundreds of cow-tales he found throughout his travels. A little bit of the Johnson County Cattle War shines through in his writing, including the legend that he wrote his famous shoot-out scene about an altercation he saw outside of the Occidental Hotel in Buffalo.

The Virginian was a legend and a time period all wrapped into one package– even now, over a hundred years after the novel was written, the author is honored in dozens of places– not just an old hotel on the plains.

Mount Wister in Yellowstone National Park shares his name, as does the literary review magazine at the University of Wyoming and dozens of places named after his stay there, like the Owen Wister room in the occidental hotel in buffalo.

Dozens of things build the man Owen Wister’s legacy, but none more than his rough cowboy.

As The Virginian would say— “When you call me that, smile.”